According to the calendar we are entering the season of fall. For Texans, this means football (hopefully) and battling mosquitoes on your campuses. This particular insects will make you itch, scratch, and sometimes even say bad words. With the help of Dr. Sonja Swiger,Associate Professor & Veterinary/Medical Extension Entomologist, AgriLife Extension this article will help explain the symptoms of West Nile Virus and encephalitis, what schools need to know about basic mosquito management and additional resources to help educate you and your staff.

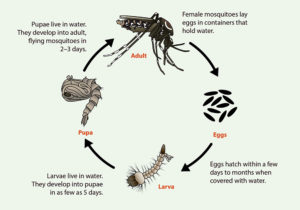

Life Cycle of Aedes aegypti and Ae. albopictus Mosquitoes (image from CDC)

Mosquitoes are of concern in the school environment because many species are painful biters and/or are capable of transmitting diseases. In the United States, the threat of developing encephalitis from mosquitoes is far greater than the threat from other mosquito vectored diseases. Encephalitis, meningitis, and other diseases can develop from the bites of mosquitoes infected with certain viruses such as West Nile, St. Louis encephalitis, LaCrosse (California) encephalitis, and Eastern equine and Western equine encephalitis. An effective control program will not eliminate all mosquitoes but will keep the population at a reasonable level and will reduce both nuisances and the risk for mosquito-borne diseases. With human cases on the rise this summer, our best defense is knowledge of the virus and mosquito management.

West Nile Virus is a mosquito-borne virus contracted through mosquito bites. Only about 60% of people who have tested positive for the virus ever knew they were being bitten by mosquitoes, so it’s advisable to just assume they are out and about daily depending on where you live in the state.

People of all ages (including children) can contract the virus. About 20% of those who contract WNV (1 in 5) will come down with what is called “West Nile fever”; less than 1% of people will develop serious symptoms referred to as “West Nile Neuroinvasive Disease” which affects the central nervous system; the other 80% of those infected develop no symptoms of the virus.

Symptoms of West Nile fever can include:

|

Fever |

Body Aches |

Rash on the trunk of the body |

|

Headache |

Tiredness |

Swollen lymph glands |

About 1 out of every 150 people with West Nile Virus will develop a severe infection resulting in encephalitis (inflammation of the brain) or meningitis (inflammation of the lining of the brain and spinal cord). Severe illness can occur in people of any age; however, people over 60 years of age are at greater risk. People with certain medical conditions, such as cancer, diabetes, hypertension, kidney disease, and people who have received organ transplants, are also at greater risk.

Symptoms of encephalitis or meningitis include:

|

High fever |

Headache |

Neck stiffness |

|

Stupor |

Paralysis |

Disorientation |

|

Muscle weakness |

Tremors |

Coma |

How Mosquitoes become infected and transmit to humans.

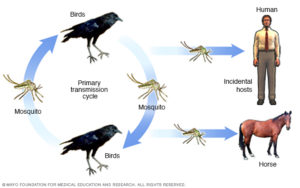

Virus transmission cycle (Image from Mayo Clinic)

After a mosquito feeds on the blood of a bird infected with West Nile Virus, the virus goes through a short growth period before it is capable of being retransmitted – as few as four days.

The infected mosquito, full of virus and ready to feed again, will look for a bird, human, or other animal for its next blood meal. This is the basic transmission cycle of the virus as it moves easily from bird (reservoir host) to mosquito (vector) and then – accidentally – on to humans or other animals. Humans, horses, or other animals do not expand virus transmission and are referred to as “dead end” hosts for the virus.

Mosquito Prevention Tactics

The best way to prevent West Nile Virus is to minimize the number of mosquitoes since that is the only way the virus moves from bird host to human in nature. Generally, the easiest way to deal with mosquito pests is to prevent them from breeding around us in the first place, and this is quite easy.

Mosquitoes need wet conditions to lay their eggs and grow from an aquatic larva into a flying adult a poor irrigation system can contribute to encourage breeding sites. HUMANS create most of the wet conditions used by mosquitoes in our state, and it is likely that many of us have mosquitoes developing in our neighborhoods and own backyards. We cannot eradicate every individual mosquito, but there are some very simple steps each of us can take to keep numbers low.

The most important single thing a school district can do is make sure school grounds are not contributing to your local mosquito populations. Check water catchment basins, storm drains, low areas, and equipment storage yards, athletic and playground equipment, especially, for places where water might be caught and held. Drain or treat with Bti dunks, or Altosid granules–both Green category insecticides.

Dense vegetation shown here can hide mosquitoes, ants and other pests make sure you are inspecting these area as well.

Mosquitoes typically rest in vegetation or other shaded sites during the day. If you have areas of vegetation or doorways where mosquitoes are a noticeable problem, consider treating such sites with a residual pyrethroid spray. This would be a Yellow category treatment and should be limited to known problem areas. Insecticides like deltamethrin, cyfluthrin, bifenthrin, and lambda-cyhalothrin can provide up to six weeks control on vegetation or building surfaces. They can be applied via hand-held pump sprayer, backpack mist blower, or power sprayer to doorways and trees, shrubs and ornamental grass around buildings and entryways. Do not allow students or staff into treated areas until sprays have thoroughly dried. Remember students cannot enter an area that has been treated with a Yellow Category product for 4 hours.

If the city or your district wants to apply ULV insecticides for pretreating sporting venues, posting and notification requirements must be followed and Yellow category justifications filed, as with any use of Yellow category product. ULV treatments usually use synergized pyrethrins (Green for products with less than 5% piperonyl butoxide), resmethrin or permethrin (Yellow). Mosquito control with such sprays is short-lived (few hours to a day) and should be conducted only when wind is less than 5-10 mph.

When it comes to IPM for mosquitoes, don’t forget educating students, parents, and staff. The district should consider notifying parents and students advising them to wear repellent to school or evening sporting events. Use of repellents on school grounds is something each school district must decide on. Personal use of repellents is not prohibited or really addressed by state school IPM regulations; however, they are addressed through the Department of State Health Services who considers repellents as part of an over the counter medication. If you haven’t done so, visit with your district’s head nurse make sure she/he is aware of your IPM program and the efforts you, your staff and your pest control contractor are doing everything they can do to help prevent mosquitoes. The Texas Department of State Health Services and many local mosquito control authorities have useful educational fliers and websites (see below) that parents should be aware of. School districts have a useful role to play in getting mosquito awareness information out to our communities. Consider linking this information in your school district’s website.

Resources and More Information

Mayo Clinic West Nile Virus Website

TX Dept of State Health Services Mosquito-Borne Disease Prevention Website and here are their kid friendly resources link

.

.