Elementary school students and their teacher prepare soil and plant vegetables in a school learning garden.

There are numerous benefits when youth participate in the Junior Master Gardener Program.

Research has shown that outdoor interests, physical activity, and good nutrition all yield positive benefits for youth. And research also shows gardening is an excellent way for young people to connect with nature and learn about personal responsibility, commitment, and teamwork.

“Through Junior Master Gardener youth programs we engage young people in novel, hands-on group and individual learning experiences that help them develop a love of gardening and an appreciation for the environment, while also cultivating their minds,” said Lisa Whittlesey, Texas A&M AgriLife Extension Service senior program specialist and director, International Junior Master Gardener Program, Bryan-College Station.

Junior Master Gardener Program

JMG is an international youth gardening program of the land-grant university Cooperative Extension Network. Both in the U.S, and internationally, the JMG program is administered by AgriLife Extension, an educational outreach agency of the Texas A&M University System.

“The JMG program also inspires youth to be of service to others through service learning and leadership development projects, and rewards them with certification and recognition”, Whittlesey said. “It lets children get involved in exploring their world through meaningful activities that encourage leadership development, personal pride and responsibility, and community involvement”.

Through the Junior Master Gardener Program, young people learn about gardening and develop a respect for nature while learning life skills such as teamwork and leadership.

She said most Junior Master Gardener group activities take place in schools around the country and are taught by teachers as a part of their classroom instruction. There are also JMG groups that learn in informal settings such as afterschool programs, 4-H clubs, scouting and summer camps.

“There are JMG-related youth gardening programs throughout the U.S. and internationally”, Whittlesey said. “There are currently JMG programs in every state and in partnership with 10 foreign countries”.

In Texas there are JMG programs in approximately 160 counties in both urban and rural areas.

“These programs give youth the opportunity to explore their world through meaningful activities that help develop useful life skills and also give a practical application to earth science and other classwork”, Whittlesey said.

The JMG program works in collaboration with teachers, school administrators, school districts, community groups, youth organizations and youth leaders to bring its programs to youth throughout the state, she said.

“We offer a variety of materials, curricula and resources for teachers and other leaders interested in using garden-related content with their students”, Whittlesey said. “There are core comprehensive JMG curricula for elementary and middle school programs and also thematic curricula such as Learn, Grow, Eat and Go!, Wildlife Gardening, and Literature in the Garden to provide engaging lessons and educational opportunities for kids.”

More information on the Junior Master Gardener program can be found at http://jmgkids.us or by contacting Whittlesey at l-whittlesey@tamu.edu.

Learn, Grow, Eat and Go!

A cornerstone of Junior Master Gardener programming is the Learn, Grow, Eat and Go!, LGEG, youth gardening curricula.

“Learn, Grow, Eat and Go! is an interdisciplinary program that integrates academics, gardening, nutrient-dense food experiences, physical activity, and school and family engagement”, Whittlesey said. “The target audience is kids in third to fifth grade, but the curriculum can be modified to suit various grade levels”.

The LGEG curriculum includes two lessons a week. Students learn about plant nutrient requirements, as well as nutrients required for the human body to function properly. They maintain and harvest vegetables from their own learning garden, plus take part in cooking activities in which they help prepare dishes using the vegetables they harvest.

“Through this linear set of academically rich, proven lessons, youth learn about plants and what they need, as well as how plants provide for our nutritional needs”, Whittlesey said. “They also engage in fun and educational activities along with the cooking activities and outdoor physical activity”.

Kids participating in the 12-week Learn, Grow, Eat and Go! program get instruction on how to make nutritious recipes using the vegetables they grow and harvest.

“The best part of collaborating with the Texas A&M AgriLife Extension Service and the Junior Master Gardener program has been the hands-on assistance, training, materials, and resources they make available to those wanting to implement a youth gardening program”, said Amalia Sollars, K-8 enrichment program coordinator for the Northside ISD in San Antonio.

Betti Wiggins, Houston ISD officer of nutrition services, said the LGEG program has been a natural fit for their youth education goals. Wiggins is responsible for managing and implementing all of Houston ISD’s school nutrition programs, which serve more than 280,000 meals to students each day at 287 schools.

“It’s about teaching our kids to be smart food consumers, along with getting them outdoors and being engaged as custodians of our food system”, Wiggins said. “We at HISD appreciate this opportunity to work with AgriLife Extension in the LGEG program and know we have found the right partners to make sure our kids understand the importance of good food and can become more food literate”.

The Learn Grow, Eat and Go! curriculum has recently been made available online as a distance learning opportunity for elementary school students. The course is $35 and is available at https://bit.ly/2RRHtdG.

“The content for the online ‘Learn, Grow, Eat and Go! for Youth’ course is very similar to the current LGEG in-person program curriculum, providing two lessons per week over a 10-week period”, said Randy Seagraves, AgriLife Extension program specialist leading the course’s online development.

There is interactive, video-based content for all 20 LGEG lessons.

“Whether it’s through school, independent learning or a virtual summer class at a distance, kids will love the hands-on lessons and activities teaching them to grow and maintain their own vegetable and herb garden and use the harvest to prepare delicious and nutritious recipes”, Seagraves said.

Teachers and youth educators can access professional development training to implement the LGEG program in their community and access the LGEG video library to support classroom instruction through https://agrilifelearn.tamu.edu/.

The complete Junior Master Gardener ‘Learn, Grow, Eat & Go!’ curriculum, designed for use by teachers in a classroom setting, is available through the Texas A&M AgriLife Bookstore at a cost of $56.

Wildlife Gardener program

Wildlife Gardener program

“The Wildlife Gardener program combines the knowledge and resources of the National Wildlife Federation and the Junior Master Gardener program, with input from teachers and students across the country,” Whittlesey said. “These combined efforts have created an integrated, engaging, one-of-a-kind experience for kids”.

She said young people can become certified as Wildlife Gardeners by taking part in a curriculum that will also help them strengthen their skills in math, science, language, and social studies.

“The goal of wildlife gardening is to show young people the importance of the natural ecosystem and teach them how to build components of a wildlife habitat within their garden”, Whittlesey said. “We also want them to gain a greater understanding of and appreciation for the wildlife in their local community. This is through project-based learning focused on gardening for the benefit of wildlife”.

Literature in the Garden program

“JMG’s Literature in the Garden program engages youth through powerful garden- and ecology-themed books that inspire learning through outdoor activities, creative expression and open exploration”, Whittlesey said.

“JMG’s Literature in the Garden program engages youth through powerful garden- and ecology-themed books that inspire learning through outdoor activities, creative expression and open exploration”, Whittlesey said.

She said the curriculum includes dozens of hands-on math, science, and language-based activities to encourage leadership development, individual responsibility, community involvement and critical thinking.

“This curriculum utilizes six Growing Good Kids Book Award-winning titles”, Whittlesey said. “It uses quality children’s literature to connect kids to gardening and the natural world. Bringing gardens and great books together is another great way to grow good kids”.

Other youth gardening learning opportunities

“We are also beginning an early childhood version on the Learn, Grow, Eat and Go! program for even younger children”, Whittlesey said.

She said Early Childhood LGEG is an easy-to-implement, garden-based curriculum for teachers of youth from the Head Start level to kindergarten.

“This is a four-week curriculum that combines learning about plant and gardening basics, understanding food and where it comes from, and why good nutrition and physical activity are necessary to having a healthy life”, Whittlesey said. “This is all done in the context of novel and effective parental engagement”.

Whittlesey said the early childhood version of the LGEG program will help youth build a love of gardening and appreciation for nature from an even younger age.

Written By: Paul Schattenberg, Communication Specialist, Texas A&M AgriLife

Controlling the pest population at your school district or community college isn’t as simple as spraying pesticides. Fighting off annoying critters without negatively impacting the health of your community and the environment requires a delicate balancing act of responsible pesticide use, staff training, and an effective school integrated pest management (IPM) program.

Controlling the pest population at your school district or community college isn’t as simple as spraying pesticides. Fighting off annoying critters without negatively impacting the health of your community and the environment requires a delicate balancing act of responsible pesticide use, staff training, and an effective school integrated pest management (IPM) program.

Wildlife Gardener program

Wildlife Gardener program “JMG’s Literature in the Garden program engages youth through powerful garden- and ecology-themed books that inspire learning through outdoor activities, creative expression and open exploration”, Whittlesey said.

“JMG’s Literature in the Garden program engages youth through powerful garden- and ecology-themed books that inspire learning through outdoor activities, creative expression and open exploration”, Whittlesey said.

This month’s newsletter is aimed at helping you out with a few resources you can use, plus some news stories you might be interested in that you can share.

This month’s newsletter is aimed at helping you out with a few resources you can use, plus some news stories you might be interested in that you can share.

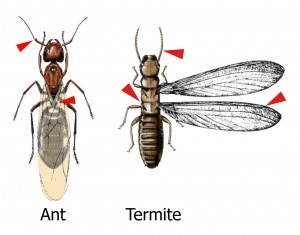

Use this diagram to train school maintenance staff in how to recognize and report termites.

Use this diagram to train school maintenance staff in how to recognize and report termites.

.

.