Written By: Rosemary Hallberg, Communication Director, Southern IPM Center

I’ve had many discussions with my colleagues about the best way to sell integrated pest management, or IPM, to the public. Although I don’t usually work with people directly on their pest management practices, I have heard some of our IPM Coordinators say, and have read in several news articles, that IPM is easier to sell to some people than to others. Why is that? Why is the organic community so successful at selling organic goods to the general public, while most people I know outside of my job don’t know what “IPM” stands for?

The answer may lie in an article that appeared in Perspectives on Psychological Sciencein 2015, titled “Improving Public Engagement With Climate Change: Five ‘Best Practice’ Insights from Psychological Science.” Although the article focuses on climate change policymaking, we can use similar principles in IPM to assist our “integrated people management,” as some of my school IPM colleagues call it.

The authors assert that most people make decisions about a social issue based on five psychological principles:

- The human brain privileges experience over analysis

- People are social beings who respond to group norms

- Out of sight, out of mind: the nature of psychological distance

- Framing the big picture: nobody likes losing (but everyone likes gaining)

- Playing the long game: tapping the potential of human motivation

While I’m not going to make any policy suggestions—as I have many colleagues who have much more experience in the IPM policymaking world than I do—I am going to try drawing some parallels between the author’s explanations of each of the 5 principles and how they might relate to our rhetoric about integrated pest management.

- The human brain privileges experience over analysis

The human brain relies on two processing systems, says the Perspectives article. One system involves the emotions and the second system involves the intellect. Most of the decisions that we make that affect our lives emanate from the emotional system, while we use the intellectual system to defend them.

People tend to prioritize things based on strong feelings. In campaigns, discussions about terrorism and children typically win over voters because they are top priorities for people. People want to feel safe and they want to protect the helpless. Many of our disinfectants are advertised next to babies or young children because the message is that they’re “safe” for the most vulnerable. Growers clamor for new herbicides after years of battling weeds like Palmer amaranth and losing money. People may buy organic products because they feel they are “safe” and “healthy,” grown “with no pesticides,” not realizing that many organic growers have to use some kind of chemical to protect their crop. How can we generate emotions about IPM products or practices? Or override the fear that without a pesticide that the crop or setting will be overrun with insects, diseases or weeds?

People tend to prioritize things based on strong feelings. In campaigns, discussions about terrorism and children typically win over voters because they are top priorities for people. People want to feel safe and they want to protect the helpless. Many of our disinfectants are advertised next to babies or young children because the message is that they’re “safe” for the most vulnerable. Growers clamor for new herbicides after years of battling weeds like Palmer amaranth and losing money. People may buy organic products because they feel they are “safe” and “healthy,” grown “with no pesticides,” not realizing that many organic growers have to use some kind of chemical to protect their crop. How can we generate emotions about IPM products or practices? Or override the fear that without a pesticide that the crop or setting will be overrun with insects, diseases or weeds?

- People are social beings who respond to group norms

When consumers see an issue as a global problem (such as climate change), they tend not to feel that their actions can make a difference. When a practice such as integrated pest management is presented as “good for the environment,” if an individual doesn’t see their neighbors following the practice, he or she tends not to pick up the practice.

However, people tend to follow the example of others that they trust or respect. I’ve talked to several Extension specialists who said that growers adopted a practice or variety after talking to their neighbors at the local hangout. Teachers talk to each other in the teacher lounge. How can we promote community acceptance and practice of IPM, whether in a farming community, school or neighborhood?

- Out of sight, out of mind: the nature of psychological distance

The APS article states that the promotion of climate change as a future consequence removes it from the public eye as something that needs to be addressed now. In fact, “immediate day-to-day concerns take precedence over planning for the future” (van der Linden et al.). The authors show this principle at work in the public belief that climate change is a distant threat that doesn’t need to be addressed now.

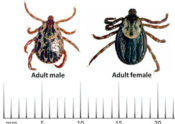

One of the main motivations behind IPM practices is resistance management. This rationale, however, is an example of something that can be perceived as a distant threat. I have lost count of the number of articles in agricultural media such as Farm Press and Growing Produce that include warnings and pleas by weed scientists and entomologists not to rely on a new chemistry once an old one has been rendered useless. However,eager to reclaim income lost the previous year, growers ignore the warnings and do what they think will rid them of the problem. In the same vein, teachers and homeowners reach for the canned insecticide when they see an ant or cockroach because they feel it will give them immediate satisfaction of the insect’s death, while neglecting to realize that a good cleaning is needed to get rid of the rest of the colony that is nesting in closet clutter or in an unmaintained windowsill. To convince people to use IPM, resistance and clutter must be seen as issues that are immediate rather than in the future.

One of the main motivations behind IPM practices is resistance management. This rationale, however, is an example of something that can be perceived as a distant threat. I have lost count of the number of articles in agricultural media such as Farm Press and Growing Produce that include warnings and pleas by weed scientists and entomologists not to rely on a new chemistry once an old one has been rendered useless. However,eager to reclaim income lost the previous year, growers ignore the warnings and do what they think will rid them of the problem. In the same vein, teachers and homeowners reach for the canned insecticide when they see an ant or cockroach because they feel it will give them immediate satisfaction of the insect’s death, while neglecting to realize that a good cleaning is needed to get rid of the rest of the colony that is nesting in closet clutter or in an unmaintained windowsill. To convince people to use IPM, resistance and clutter must be seen as issues that are immediate rather than in the future.

- Framing the big picture: nobody likes losing (but everyone likes gaining)

Whether it’s climate change, pest management, pollinator protection or world peace, conversations around change involve the idea of “loss.” In fact, often the loss is the part of the discourse that’s heard when experts present the actions to take to prevent the future problem. To slow down or reverse climate change, people hear that they need to give up their automobiles. To maintain use of a pesticide, growers hear that they need to spend more time on insect or weed management. To ensure pollinator survival, growers and homeowners hear that they’re going to lose a pesticide that has always worked. So in response, many people feel that the status quo is better than having to give up something.

When used effectively, IPM can ultimately save money and time. However, those promises fly in the face of principle #3 (out of sight, out of mind). Many people aren’t willing to lose something today to gain something tomorrow. Growers will use an herbicide again and again until the weeds don’t respond. Homeowners will use a canned insecticide again and again until they realize that they’re not ending the infestation. How can IPM professionals present IPM as a win-win that gives an immediate return?

- Playing the long game: tapping the potential of human motivation

People respond to one of two different sources of motivation: intrinsic and extrinsic. Extrinsic incentives include external rewards such as cost savings, time or profits. Intrinsic incentives include values and morals. Farmers who participate in pollinator protection collaborations do so because the reward appeals to their extrinsic—they need pollinators for fruit set—and intrinsic—they care about the environment and want to protect it—values. Some home gardeners refrain from using commercial pesticides because they think it is safer for their family (an extrinsic appeal) and good for the environment (an intrinsic appeal). IPM specialists focus on both extrinsic and intrinsic motivations when appealing to audiences to use IPM.

People respond to one of two different sources of motivation: intrinsic and extrinsic. Extrinsic incentives include external rewards such as cost savings, time or profits. Intrinsic incentives include values and morals. Farmers who participate in pollinator protection collaborations do so because the reward appeals to their extrinsic—they need pollinators for fruit set—and intrinsic—they care about the environment and want to protect it—values. Some home gardeners refrain from using commercial pesticides because they think it is safer for their family (an extrinsic appeal) and good for the environment (an intrinsic appeal). IPM specialists focus on both extrinsic and intrinsic motivations when appealing to audiences to use IPM.

I’m sure that many IPM specialists can think of examples where all of these psychological principles have been at work, but the one that has been weighing on my mind the most since I read the tragic story in Delta Farm Press is the situation over dicamba in Arkansas. Soybean growers suddenly had a new technology that seemed to give them access to a new use for a powerful herbicide. Although weed scientists, consultants and industry representatives gave strong warnings that growers were not to spray dicamba on top of the new soybean variety, memories of weeds crowding out the previous year’s crop, in addition to the promise of new profits, made the temptation to ignore warnings and spray the crop too hard to resist. Growers who were on the fence about whether or not to spray heard from other growers who decided to use the product illegally and decided to join the group. Some growers focused on their own gains or losses and didn’t consider that their illegal dicamba use might cause drift that would destroy their neighbors’ non-GMO crop. Ultimately, tensions between both sides reached a head and resulted in the death of one grower and stricter regulations assigned by the Arkansas Plant Board.

Many of my colleagues have told me that their specialty is science, not psychology or sociology. As someone whose specialty is writing and not science, I understand the reasoning. However, sometimes science isn’t enough to convince a farmer who fears for his or her crop and is battling several other environmental challenges like drought or temperature shifts. Science may not convince a schoolteacher who is worn out by the end of the day that he or she needs to take extra time to clean out the closet. Convincing the public that IPM is worthwhile to support will involve more than simply integrated pest management principles. It will take an understanding of the emotional motivations that lead people to act as they do. It will involve Integrated Psychology Management.

Source: van der Linden, S., Maibach, E., and Leiserowitz, A. (2015). Improving public engagement with climate change: Five “best practice” insights from psychological science. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 10:6, 758-763, doi: 10.1177/1745691615598516

.

.